People

Hugh Maxwell

1733-1799

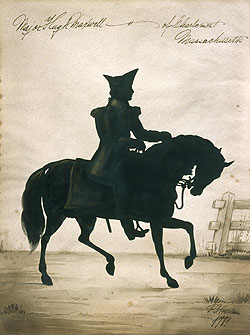

Hugh Maxwell

By Frederick Chapman, 1781, Harlem, NY. Courtesy Historic Deerfield, Inc., Deerfield, MA

Prologue

Hugh Maxwell was an American surveyor and farmer from Charlemont, Massachusetts. Born in Ireland in 1733, he migrated with his family to the Massachusetts Bay Colony and settled in town of Bedford, about 15 miles from Boston. In 1760, when he was 27 years old, Hugh married Bridget Munroe of Bedford. By 1772, the couple would have six children. As a young man, Hugh fought in several campaigns during the French and Indian War, including the capture of Fort William Henry by the French in 1757.(1) Wartime recruitment bonuses and good pay were attractive incentives for young men like Hugh who needed money to buy their own land or to get started in business. Perhaps the money he received for his militia service helped Hugh to buy land in northwestern Massachusetts, in the town of Charlemont. Hugh, and his family made the 100-mile journey from Bedford in the fall of 1772.(2)

Like most of his Charlemont neighbors, Hugh Maxwell was not well-to-do, but he quickly gained their respect. He could offer first-hand accounts of the turbulent politics and protests in Boston and other eastern towns. His experiences in Bedford had evidently turned Hugh into a strong Whig, or Patriot. He was among the thousands of men who organized themselves into "Minute Companies" on the eve of the American Revolution. In April 1775, Lieutenant Hugh Maxwell marched to Cambridge with his Charlemont militia company. Maxwell remained at Cambridge, where he jjoined Colonel William Prescott's regiment. In June 1775, Hugh fought and was wounded at the battle of Bunker Hill.(3)

In November, 1776, Captain Hugh Maxwell was ordered to raise a company of 86 "able-bodied and effective Men" to serve in the Continental Army "'til the End of the present War or for the Term of three Years." He was commissioned as a major on July 7, 1777. In addition to the siege of Boston, he was present at the battles of Trenton, Princeton, Saratoga, and Monmouth. By the end of the war, he was Lieutenant Colonel of the Third Massachusetts Regiment of Major General William Heath's brigade.(4)

American troops marched under flags of all sorts during the Revolution, such as this

red, eight-pointed star and homespun linen fragment of a flag owned by Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Maxwell.

More info

By the spring of 1783, Colonel Maxwell's regiment was stationed at West Point, New York. The long war was all but over and the peace commissioners were working through the final negotiations. Hugh and his men were more than ready to go home, but worried about how they would manage to live when they were at last able to leave the army. The officers and enlisted men had gone months, and in many cases, years without being paid for their service. The United States treasury was empty and Congress lacked the means and the power to raise money. General George Washington had managed to avert a near-mutiny by Continental Army officers at Newburgh but the problem of how to disband the army without being able to pay them remained. Deeply concerned for his men, Colonel Maxwell wrote an eloquent appeal to William Stickney of Massachusetts on their behalf. Enlisted men and officers alike were, he reported, tremendously excited by the rumors "that we are on the eve of a peace…it is what we wish for with the greatest anxiety." If peace was indeed coming, however, Maxwell wondered "what you will do with your army? Many will say disband it at once. I say so too."(5)

But, Maxwell continued, "will you turn us into the wide world to seek our fortune like fortune-hunters, without money or friends, after we have served you eight years in your wars? after spending the flower of our days in the service of our country, and under God been the means of freeing it from the greatest danger that it could fear?" Maxwell reminded Stickney that what little pay the army had received at this point had not been in cash. Congress and the states had instead issued soldiers paper securities based on a future promise by the government to redeem them in cash. Such small payments were "of very little service to us." Even worse, many men had already had to part with such securities "on very disadvantageous terms" in order to raise the cash they desperately needed for themselves and their families. Faith in the government's pledge to redeem the securities was so low that even those who had been able to hang on to them were ill-served, "though there are but few of us that have been able to keep them."(6)

As it turned out, Congress decided to furlough most of the men instead of discharging them. This allowed the government to avoid the danger of disbanding all at once a large group of destitute and potentially violent men. The furloughed soldiers marched under the tight control of their officers. Small groups would depart for their various communities as they neared them. Congress justified the furlough strategy by arguing that, while an army in the field was no longer necessary, it might be needed if negotiations broke down or if the British army still occupying New York City refused to leave peaceably. Once they were dispersed, Congress disbanded the army and paid soldiers in interest-bearing government securities of the kind Colonel Maxwell had described to Stickney. Hugh's regiment was furloughed in June, 1783 and was disbanded five months later. For the small number of men disbanded at West Point, Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris negotiated a hasty cash loan so that each man would receive one month's pay with the remainder to be issued in public securities. At General Washington's request, the government also allowed soldiers to keep their army-issued weapons, uniforms and equipment.(7)

After his discharge, Colonel Maxwell maintained his ties with fellow officers and soldiers. He immediately joined the Society of the Cincinnati, a fraternal organization created by and for Continental Army officers and their male descendents. The personal bonds he had formed remained strong; Maxwell expressed his admiration for his commanding officer General Heath when the section of Charlemont in which Maxwell lived was incorporated as the new town of Heath.(8)

General Henry Knox

signed this certificate certifying that Colonel

Hugh Maxwell was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati, formed to maintain the "Bonds of

Perpetual Friendships" among Continental Army officers.

More info

True Faith And Allegiance To The Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Already a respected figure in town before the war, Hugh Maxwell's distinguished army service and rank further increased his status. Upon his return, he was appointed a justice of the peace, a post he held until he died. He also held a number of town offices, and actively supported the church. In company with most high-ranking officers of the Continental Army, Colonel Maxwell opposed the movement during the winter of 1786-87 that later became known as Shays' Rebellion. In contrast to nearby Colrain, not a single Heath man took up arms against the government. That spring, Selectmen Hugh Maxwell and Asaph White submitted a reimbursement request to the state for money the town had spent on rations for 11 men who had traveled to defend the United States Arsenal at Springfield. As a justice of the peace, Colonel Maxwell administered the Oath of Allegiance to former insurgents. Under the terms of the pardons offered under the Disqualification Act, Hugh also was authorized to confiscate oath takers' muskets.

Epilogue

Community admiration did not translate into economic prosperity. Hugh had never been a wealthy man. The expense of supporting a large family of seven children combined with lack of compensation for the many years of service in the army made his final years difficult ones financially. Hugh traveled to Philadelphia in 1795, where he petitioned the United States Congress unsuccessfully for a pension for his wartime service. In a letter home to Massachusetts he expressed frustrations shared by many veterans of the Revolution.

I do not lament that I have fought many a hard battle for this country. I do not lament that in sundry instances I have suffered almost every thing but death, in the service of these states, for I did my duty like an honest man. But still did I expect the promised reward. Still am I persuaded a reward from America is my due. Half-pay as a Lieutenant Colonel is what I challenge, as my honest reward, from the beginning of '84, during my natural life; it is due to my wife; it is due to my children. And may God grant that this or some future Congress may see it to be so, and conduct accordingly.(9)

In 1799, in an attempt to rescue his worsening finances, Hugh decided to invest in an export venture, shipping horses to the West Indies. He became extremely ill on the homeward voyage. Eagerly anticipating his return, his wife and children instead received the sad news that Colonel Hugh Maxwell had died at sea on October 14, 1799, at the age of 67.(10)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page