People

John Williams

1751-1816

John Williams

© 2008 Bryant White

Prologue

John Williams was born in Deerfield, Massachusetts in 1751. Both of his parents were from well-connected Connecticut River Valley families. John's father, Elijah, was the son of the Reverend John Williams. It was this older John who was captured along with his entire family and many others in a devastating raid on Deerfield by the French and their Native allies in 1704. Elijah took over the family home when his father died in 1729, married Lydia Dwight of Hatfield, and proceeded to have seven children. Lydia died in 1749. Less than a year later, Elijah married Margaret, a member of the powerful Pynchon family of Springfield. That Lydia's death had left Elijah with five children all under the age of 10 may have played a role in prompting him, like many other bereaved spouses in this period, to remarry quickly. John, or "Jack," was born a year later.(1)

The youngest of eight children, John grew up in an active household. His father Elijah was prominent in town affairs and served as an officer in the colonial militia during the French and Indian War. Major Williams was also a successful businessman. In addition to his extensive mercantile ventures and retail activities, he operated a tavern out of his house. When John was nine, his father built a fashionable new house. He also moved an old cider mill onto his lot and turned it into a store. The two-story building soon became a crossroads for civilians and soldiers throughout the county. Major Williams' prosperity enabled him to send his older son Elijah, Jr. and John to his alma mater, Harvard College. After graduating in 1769, John decided, like his older brother, to become a lawyer and briefly practiced in Salem. When his father died in 1771, John came home to Deerfield and took over the store with his sister Eunice. In 1774, on the eve of the American Revolution, John married Elizabeth Orne of Salem. He was twenty-three years old.(2)

A Loyal Subject

John had grown up as a British subject. He had witnessed his father's loyalty to Great Britain, including military service. As a student at Harvard and then a young lawyer in Salem, he was aware of the escalating protests against Parliament's colonial policies. Like his neighbors Elihu Ashley and Jonathan Judd of Southampton, John may have felt distaste and alarm at the turbulent nature of Whig politics. He may have been influenced by the example of his older brother, Elijah Jr., who was a Captain in the British Army. Whatever the reasons, John Williams emerged during the Revolution as an adamant and vocal Loyalist. Throughout the war, Deerfield was almost evenly divided between Whigs who supported independence, and Loyalists who wanted to remain part of the Empire. Condemned as "Tories" by their opponents, Loyalists like John Williams were regarded with suspicion and often became targets for open hostility.

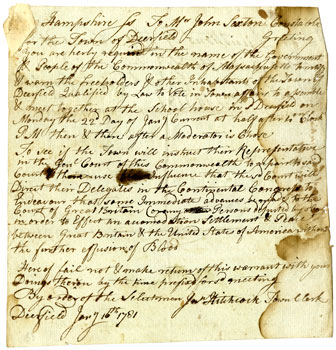

His family's regional prominence combined with encouragement from likeminded residents helped make John an aggressive Loyalist. His outspoken disapproval of the war persisted well after it had become a war for independence. Following the Continental Army's spectacular victory over the British Army at Saratoga, New York, Britain sent a peace commission to Congress. Full of concessions, the British proposal had asked only that the Americans renounce independence and return to the Empire. Fresh from ratifying the French treaty of alliance, the United States ignored the offer. To Loyalists like John Williams, the Americans had squandered an opportunity to bring an unnatural rebellion to an honorable conclusion. John refused to give up, however. In January, 1781, he worked with Elihu Ashley's brother, Jonathan, and Seth Catlin to force a resolution through the Deerfield town meeting. The resolution instructed the town's representative to the General Court in Boston to

use his Influence that the sd Court will Endeavour that some Immediate advances be made to the Court of Great Britain (or Persons deputed by sd Court) in order to Effect an accommodation Settlement & Peace between Great Britain & the United States of America without the further effusion of Blood(3)

In the middle of the Revolution, John Williams, Jonathan Ashley and Seth Catlin of

Deerfield engineered town resolution instructing their representative to the General Court

to sue for a settlement and peace with Great Britain.

More info

Convinced that he was in the right, John seems not have anticipated the hostile reaction of the Massachusetts Legislature, whose members responded to the Deerfield's startling resolution with an angry resolution of their own. It appeared to the members of the General Court that Deerfield harbored three men who were "Disaffected to the United States in General, & of [Massachusetts] in particular." The General Court accused these same men of "artfully propagating the most dangerous principles" and of "using their utmost efforts …to withdraw the good people of this Commonwealth from their allegiance to the government thereof." The February 10 resolution demanded that John Williams, Seth Catlin and Jonathan Ashley appear before the General Court to answer for their actions in promoting the Deerfield resolution and the sentiments it contained.(4)

Even now, John Williams refused to be intimidated. Advised by a friend to think for at least five minutes before responding to any question, John pondered for five minutes before giving his name. He then took an additional five minutes before informing the General Court of his residence. John's defiance did not improve his situation. The legislature ordered all three men to appear at the Superior Court in Springfield in September. Escalating alarm and anger over Loyalist efforts to control Deerfield affairs, however, brought matters to a head the next month. Based on March reports from town residents "well affected to the American Cause of Liberty and virtue" that Tories were subverting the town's government, Governor John Hancock ordered that Williams, Catlin and Ashley be seized and jailed in Boston.(5)

News of their imprisonment spread quickly. Word of John's ordeal reached John's brother, Captain Elijah Williams, who was serving with the British Army. Elijah anxiously wrote to a brother-in-law pleading for information. At the mercy of rumors and speculation, Elijah was "in great uneasiness an …at this time from the Reports in very great Doubt" whether his brother Jack was even alive.(6)

The three men spent over a month in prison. They petitioned the General Court for release, citing family circumstances and their own ill health. John Williams appealed for mercy and understanding. He had left his wife and young children without essential support and male protection, as there was not "a male person in the family more than 8 years old." Williams had a "slender constitution & small share of health at ye best" and his confinement prevented him from "using ye proper means for his recovery." Despite the conspicuous lack of assurances of loyalty to the present government, the General Court released the prisoners on April 24 on £2,000 bail apiece and ordered them, as before, to appear before the Supreme Judicial Court at Springfield. The whole arrangement depended upon the prisoners' " good Behaviour towards all the people of this Commonwealth." Williams, Ashley and Catlin were particularly warned not to "do or say any thing to the Injury of this or the United States, [or] against the Independence thereof."(7)

In spite of his brother's worst fears, Jack returned to Deerfield, but in broken health; Jonathan Ashley died four months after his release. The case against them was never filed at the Springfield court. Bowing to the inevitable, John Williams and Seth Catlin took an oath of allegiance to the government.(8)

Boom and Bust

Two years later, the war was ending at last. John may have felt a surge of optimism as he recorded transaction after transaction throughout the fall of 1883 in the day book for his store. Friends and neighbors came to buy, eager to make up for lost time and replenish their homes, farms and businesses with goods that had been either unavailable or too expensive during the war. Like his father before him, John worked to establish trade relationships and connections far beyond Massachusetts. In addition to his trade with the West Indies in lumber, barrel staves, and livestock, Jack decided to break into trade with China. He put out a call to customers for wild ginseng, a plant whose root was prized in Asia for its medicinal properties. Flushed with optimism and good feeling, Deerfield once again turned to John for political leadership. Elected in 1783 to represent his town at the Massachusetts General Court, John may have felt that the hard times were at last behind him, his family and his community.(9)

Unfortunately, this was not the case. The upswing in business ended as the post-war boom turned into a post-war bust. Great Britain closed its West Indies ports to American shipping. Too much ginseng glutted the market and John's investments suffered there as well as in other transatlantic markets. Personal tragedy punctuated these business reverses when his wife Sarah died in 1785. John remained a widower until 1802, when he married Eunice Woodbridge. As for his election to the General Court, the Massachusetts legislature was incredulous that Deerfield had chosen to send a man who only two years before had been imprisoned as an enemy of the United States. The legislature refused to seat him. It was a mark of the respect he commanded and his status as a community leader that Deerfield refused to accept the General Court's decision and continued electing John until at last he was allowed to take his seat among the other representatives, where he served three terms.(10)

Business at John Williams' store, so bustling the previous fall, had dwindled

alarmingly by 1784.

It is not hard to imagine John Williams' reaction to the rise of the Regulator movement in the fall and winter of 1786. Like his old friend Seth Catlin, he had little respect for mobs. The same conservatism that marked his actions during the Revolution led him to support the Massachusetts government during this crisis. The work of the Philadelphia Convention to establish a stronger, more fiscally stable federal government also likely met with his approval.

Epilogue

Like many other former Loyalists, John Williams adapted to the new political climate following the ratification of the new United States Constitution in 1789. He represented the town in the General Court for several more terms, acted as Register of Deeds, and served continuously as a Justice of the Peace from 1791 until his death. John was less fortunate in his personal life. His two surviving sons both died in early adulthood. As for John himself, he seems never to have fully recovered from his ordeal and incarceration during the Revolution. Plagued by ill health, he died in 1816 at the age of 65.(11)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page