People

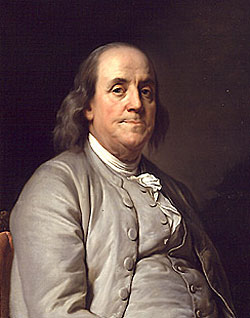

Benjamin Franklin

1706-1790

Benjamin Franklin

By Joseph Siffred Duplessis (1725-1802),

oil on canvas, circa 1785.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Gift of The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation.

Prologue

Benjamin Franklin ranks among the most recognizable leaders of the American Revolution. His signature appears on the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Paris ending the American Revolution in 1783, and the United States Constitution. It is hard to imagine the American Revolution without Franklin; it is harder still to imagine how it could have succeeded without him. After spending much of the war abroad in France, first to negotiate the crucial French alliance and then the peace terms with Great Britain, Franklin returned to Pennsylvania in 1785. Despite the fact that he was 79 years old, ailing and worn out, he was elected president of the Executive Council of Pennsylvania within weeks of his arrival.(1)

A Dangerous Insurrection

Franklin came home to difficult times. Pennsylvania and the other new republics of the United States were struggling to remain solvent and pay their large war debts, including millions of dollars in loans Franklin had negotiated from France. Pennsylvania's own war debt included over half a million dollars in interest-bearing certificates originally issued in lieu of cash to pay its soldiers in the Continental Army. Political tensions ran high. Controversy swirled around attempts by a conservative faction to reform Pennsylvania's constitution, which Franklin had helped draft in 1776. This group wanted to replace the state's unicameral legislature with an upper and lower house, and to abandon the 12-member Executive Council in favor of a single governor. Others insisted that these attempts to "reform" the 1776 constitution were part of a thinly-disguised plot hatched by propertied elites to wrest control of the government from the people of Pennsylvania. Franklin was elected to the Council in hopes that he could engineer a compromise between those supporting the current constitution and their opponents. The turbulent conditions of Pennsylvania politics and the role he was expected to play dismayed Franklin. He confessed to Thomas Paine that it was a "Business more troublesome than any I have yet quitted." This was a gloomy assessment indeed, considering the trials and challenges Franklin had faced during his years abroad during the darkest days of the Revolution.(2)

The fiscal and political crises in Pennsylvania may have made Franklin especially sympathetic to the beleaguered Massachusetts government in 1786-87. News of the government militia's success in the bloody encounter at the United States Arsenal prompted a relieved President Franklin to congratulate Governor James Bowdoin on "the happy success" of Massachusetts' "wise and vigorous measures for suppression of that dangerous insurrection." Interestingly, Franklin singled out the Massachusetts Constitution for special praise although it differed in key respects from the Pennsylvania Constitution he had helped create. Even more interestingly, some Massachusetts regulators sought to reform their constitution by eliminating the upper house, or senate, which would make it resemble more closely the Pennsylvania Constitution. Perhaps Franklin had reconsidered the virtues of a bicameral legislature and a single executive in the light of his recent experiences as the leader of the Executive Council. He heaped praise on the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. It was, in Franklin's opinion, "one of the best in the union, perhaps I might say, in the world."(3)

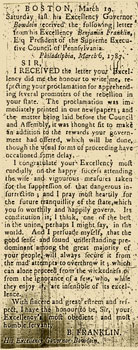

The Hampshire Gazette printed this letter from Benjamin Franklin congratulating

Governor Bowdoin on successfully suppressing the "dangerous insurrection."

More info

Franklin had no sympathy for "the mad attempts to overthrow" the Massachusetts Constitution or "the wickedness and ignorance of a few, who, while they enjoy it, are insensible of its excellence."(4) Franklin assured Governor Bowdoin that the Massachusetts proclamation offering a reward for the leaders of the insurrection had "been immediately printed in our newspapers." In fact, the government of Pennsylvania had increased the rewards:

the matter being laid before the Council and Assembly, it was thought fit to make an addition to the rewards your government had offered.(5)

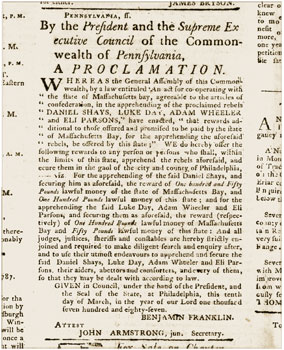

Accordingly, on March 10, 1787, the General Assembly and Council of Pennsylvania issued their own proclamation offering an additional £100 for the capture of Daniel Shays and £50 more apiece for the capture of Luke Day and other "proclaimed rebels." Signed by Franklin, the Pennsylvania proclamation sternly ordered all judges, justices, constables and sheriffs to apprehend not only the Massachusetts rebels but also "their aiders abettors and comforters, and every of them, so that they may be dealt with according to law."(6)

On March 10, 1787, President Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania issued a proclamation

offering additional rewards for the capture of Daniel Shays and other

Massachusetts "rebels"

More info

Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington, DC Prints and Photographs

Divisions

A Rising Sun

Two months after signing the proclamation, Benjamin Franklin began attending the national convention at Philadelphia charged with revising the Articles of Confederation. As the oldest member present and as the President of the host state, Benjamin Franklin had intended to nominate George Washington to chair the convention. When rainy weather combined with ill health prevented Franklin from attending that day, the Pennsylvania delegation collectively nominated Washington. Never known as a powerful orator or a domineering presence, his advanced age and poor health further limited Franklin's active participation in the debates and business of the convention. Through the oppressive heat of a Philadelphia summer, Franklin tried to foster a collaborative spirit of compromise among the delegates. This was not always easy. The convention quickly decided to abandon the Articles of Confederation entirely, and creating a new plan of government was a contentious process. Franklin made only a few speeches, which others delivered since he could not stand for extended periods. Franklin did recommend that the new constitution require members of the executive branch constitution to serve without pay. This would, he hoped, prevent the profit-based, office-seeking that had corrupted the British government. According to James Madison of Virginia, no one found this suggestion either expedient or practicable, but the delegates received it politely as a courtesy to Franklin.(7) In the end, Franklin endorsed the proposed constitution because the system of government it laid out approached "near perfection" as nearly as it could, although in the same speech he confessed he did not "entirely approve this Constitution at present." He urged those who shared his reservations to join him in signing the finished document "to make manifest our unanimity." As the delegates came forward to sign, Franklin observed that the sun carved into the back of the chairman's chair could be interpreted as either a rising or a setting sun. He now had "the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting sun." The most famous remark concerning the proposed constitution attributed to Franklin was a statement he supposedly made to a woman who asked him what sort of government the delegates had produced. Franklin allegedly replied, "A republic, Madam, if you can keep it."(8)

Epilogue

Franklin never lost his essential faith in the United States and its experiment in free government. His reaction to Shays' Rebellion, however, revealed that Franklin, like Samuel Adams, had little patience for those who he believed sought to undermine or overthrow a government constituted by and for the people. In 1790, Pennsylvania revised its state constitution, introducing many of the elements found in the new federal Constitution. In that same year, Benjamin Franklin died in Philadelphia at the age of 84.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page