People

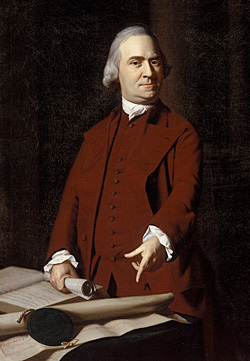

Samuel Adams

1722-1803

Samuel Adams

By John Singleton Copley, about 1772. Photograph copyright September, 2008. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, MA

Samuel Adams was best known as an influential Massachusetts politician and popular mobilizer. Unsuccessful in business, Adams' true gifts and passions lay in politics. An outspoken critic of Britain's colonial policies, he was elected to the Massachusetts General Court in 1765. He organized the Committee of Correspondence, played a central role in the Boston Tea Party in 1773, attended both Continental Congresses, and signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. In 1779, along with his cousin John Adams and James Bowdoin, he helped craft the Massachusetts Constitution. He attended the Massachusetts state Constitutional Convention in 1781, and would serve as governor from 1793-1797.

Adams was among the earliest and most persistent advocates for resistance to Britain. In 1772, he declared in "The Rights of Colonists" that "Among the natural rights of the Colonists are these: First, a right to life; Secondly, to liberty; Thirdly, to property; together with the right to support and defend them in the best manner they can."(1) Adams' revolutionary beliefs and sentiments would not, however, translate into sympathy for the actions of Daniel Shays and other Massachusetts Regulators in 1786 and 1787. As far as Adams was concerned, the contrast between the colonial protests and rebellion of the 1760s and 1770s and the court closings and protests of 1786 could not be greater. For Adams, the key difference was that the revolutionaries had been resisting the tyranny of a monarchical power. By 1786, the government was safely in the hands of the people of Massachusetts: "A commonwealth or state is a body politic, or civil society of men, united together to promote their mutual safety and prosperity by means of their union."(2) In his eyes, the Regulators were rebelling against this "civil society of men" rather than working with them to promote the good of the union, and they should thus be dealt with harshly. Adams therefore strongly recommended that the leaders of the insurgents be immediately executed:

in monarchies the crime of treason and rebellion may admit of being pardoned or lightly punished, but the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death.(3)

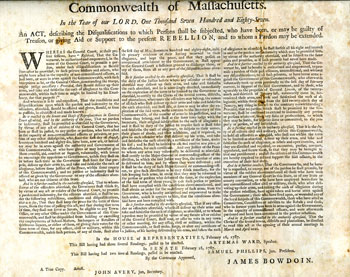

This Disqualification Act was passed by the House and Senate of Massachusetts on

February 16, 1787. It laid out the process by which former Regulators could be pardoned.

More info

Samuel Adams also called for jailing all who had taken part in what he clearly considered an unlawful rebellion, but as General Benjamin Lincoln pointed out, there were not enough jails in all of New England to hold that many people. Rather than following the heavy-handed course of action Adams prescribed, Governor Bowdoin and the Massachusetts General Court opted instead for a mix of lenient and strict measures. The state passed a Riot Act, which severely punished rioters, and a Militia Act, which called for the execution of any militia officer or soldier who had taken up arms against the state. Yet, the Legislature also successfully helped to defuse the situation by giving all rank-and-file miscreants the opportunity to repent and take an oath of allegiance to the state through the Disqualification Act over the winter of 1787. John Hancock's election as governor in the spring of 1787 signaled a still more lenient approach; in June, 1787 the popular governor issued a proclamation pardoning virtually everyone who had taken part in the rebellion.

For Adams, the strength of the Massachusetts Regulation was one more indication that the people of the state lacked the frugality and virtue necessary to sustain the free Massachusetts republic he had hoped would be a "Christian Sparta." His disappointment did not, however, translate into support for a stronger federal government. In a letter to Richard Henry Lee in 1787, Adams criticized the new, proposed United States Constitution:

I confess, as I enter the Building I stumble at the Threshold. I meet with a National Government, instead of a Federal Union of States.(4)

Adams was an influential delegate to the Massachusetts ratifying convention. Despite his initial misgivings, he supported the vote to ratify the Constitution but insisted on recommending amendments that would rectify the lack of a bill of rights, an omission he considered a major flaw. Adams remained active in Massachusetts politics, serving as governor from 1794 – 1797 before his death in 1803. A statue erected in Faneuil Hall, Boston in 1880, bears this inscription:

Samuel Adams 1722-1803 - A Patriot - He organized the Revolution, and signed the Declaration of Independence. Governor - A True Leader of the People…A statesman, incorruptible and fearless.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page