People

Benjamin Lincoln

1733-1810

Benjamin Lincoln

By Charles Willson Peale, from life, c. 1781-1783. Courtesy Independence National Historical Park, Philadephia, PA

Prologue

Hingham, Massachusetts, had been home to generations of Lincolns by the time Benjamin Lincoln was born in 1733. A prominent farmer, Benjamin's father was a Colonel and served on the Governor's Council as well as in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. When Benjamin was 23, he married Mary Cushing. They would have 11 children.(1) The senior Lincoln tried to steer a moderate course politically, reluctant to align himself with either strong Loyalist or Whig factions. His son, however, displayed no hesitation in throwing in his lot with the Whigs. Already a major in the colonial militia, Benjamin was elected to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, a shadow government formed in opposition to the Crown-controlled General Court.

Benjamin Lincoln soon caught the attention of the commander-in-chief of the newly-formed Continental Army, General George Washington. Lincoln received an appointment from the Continental Congress as a Major General. Wounded during the Saratoga campaign in October 1777, he recovered but with a limp he would keep for the rest of his life. Following the defeat General Burgoyne's army at Saratoga, Lincoln was promoted commander of the southern department of the Continental Army.

General Lincoln participated in the Saratoga Campaign that ended with the stunning

defeat of British General John Burgoyne in October, 1777.

His subsequent defeat at Charlestown, South Carolina, in May 1780 was a bitter pill for General Lincoln personally and a disaster for the United States.(2) Denied the courtesy of the customary honors of war allowed a defeated enemy, Lincoln's army was forced to march out of Charlestown without flags flying, weapons shouldered or playing a British march. (Honors of war included the privilege of playing a tune favored by the enemy as a gesture of defiance by the defeated force.) Following a prisoner exchange, General Lincoln returned to the Continental Army. He was present at the Battle of Yorktown, where his painfully-gained experience in siege warfare made him a valuable resource. When General Cornwallis surrendered, General Washington denied him the honors of war, stating that the terms for the defeated army would be the same as those forced upon the American army at Charlestown. In a heavily symbolic gesture, Washington refused to receive the sword of surrender, indicating that it be offered to General Lincoln.

Benjamin Lincoln maintained the confidence as well as the personal esteem of the General Washington through the remainder of the war. In 1781, the Congress appointed him as the first Secretary of War under the Articles of Confederation. Given the condition of the treasury (empty) and the state of the economy (chaotic), Lincoln's assignment was challenging, to say the least. His struggle to maintain the army as the war wound down placed him at the center of the demobilization crisis. How could Congress discharge enlisted men and officers when it lacked the means to pay them? Some officers tried to convince their comrades that Congress should and must be held to the promises of payments and pensions they had promised to the officers of the Continental Army. General Washington defused the "Newburgh Conspiracy" with a well-timed address at the camp at New Windsor, New York, but the problem of disbanding the army remained. General Lincoln met with General Washington to go over Congress' plan to demobilize the army. The centerpiece of the strategy was to grant enlisted men indefinite furloughs rather than immediate discharges, accompanied by three months pay of what were in many cases years of delayed payment.(3)

The ties forged among Benjamin Lincoln and other officers of the Continental Army through years of shared struggles and hardships as well as victories were strong. The knowledge that they were parting, perhaps forever, made the end of the war bittersweet. Lincoln and dozens of fellow officers met at Fraunces Tavern in New York City on December 4, 1783. With tears in his eyes, General Washington shook hands with each man, and one observer recalled that "I do not think there were ever so many broken hearts in New York as there were that night."(4)

To retain and honor the close bonds they had formed, General Henry Knox proposed that they form a "Society of Cincinnati." The name Cincinnati was a reference to the legendary Roman hero, Cincinnatus, who had saved Rome from invasion but then freely chose to renounce his power and returned to his farm. Membership would be limited to veteran officers of the Continental Army. Upon their deaths, membership would pass to the eldest direct male descendent. General Lincoln was one of the founders of the society and was the president of its Massachusetts branch. He also remained in contact with members in other states, including George Washington, who, like Cincinnatus, also had returned to his farm at the end of the war.

Benjamin Lincoln and other veteran officers formed the Society of the Cincinnati to

maintain the ties they had formed during the war. This diploma belonged to Hugh Maxwell

of Charlemont; it is signed by the Society's president, George Washington.

More info

Tumults and Insurrection

When armed protesters marched to close courts across Massachusetts, Benjamin Lincoln was quick to condemn their actions. The Massachusetts branch of the Society of the Cincinnati lost no time in criticizing the Regulators and their tactics. A set of resolves passed unanimously and immediately signed by its president referred to the court closing and other protests as illegal "commotions" that could only "interrupt the peace of society, and threaten destruction to the Constitution and Laws." The Cincinnati also called upon true citizens to defend the state: "At this alarming period, when every publick and private right is invaded, when our constitution of government, that work of labour and of blood, is shaken to its foundation, it is the duty of every individual, and of every class of citizens to stand forth in their defence."(5)

Of particular concern to Lincoln and other Cincinnati members was the news that "some officers and soldiers deluded by the councils, may have joined in the measures of those abandoned men who have in the most flagitious manner invaded the peace and good order of government." The Society,

impelled by a tenderness to the reputation and happiness of such, do in the strongest and most solemn manner intreat them to desist from these dangerous and disgraceful proceedings, and conjure them by the honour they have acquired in the field, by their regard for the feelings and reputation of their brethren, and above all by the love they bear their country and posterity, to listen no longer to the councils.(6)

Events continued to spiral out of control and caught the attention of those outside the state. George Washington wrote to Lincoln from Virginia, asking, "Are your people getting mad?" Lincoln's answer was hardly reassuring:

"Are your people getting mad?" Many of them appear to be absolutely so if an attempt to annihilate our present constitution and dissolve the present government can be considered as evidence of insanity.(7)

In fact, Lincoln continued, the situation could hardly be worse. He saw "little probability" the disorders would cease and "the dignity of government supported without blood shed. When a single drop is drawn the most prophetic spirit will not, in my opinion, be able to determine when it will cease flowing."(8)

As to the cause of the unrest, Lincoln believed that "the want of industry economy & common honesty seem to be the causes of the present commotions." There also was great complaint over the devaluation of paper money, the extent of taxation, and the cruelty of tax collectors. Lincoln explained that the "disaffected" stopped the courts from sitting.

This they hoped to do untill they could, by force, sap the foundations of our constitution and bring into the legislature creatures of their own by which they could mould a government at pleasure and make it subservient to all their purposes and when an end should be put thereby to public & private debts, the agrarian law might follow with ease. In short(9)

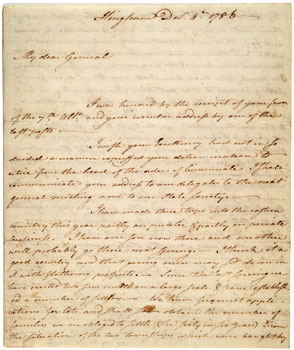

Benjamin Lincoln wrote this letter in response to George Washington's anxious question,

"Are your people getting mad?"

More info

Lincoln's letter was delayed in mailing. In a postscript dated January 21, 1787, he added that he had just been placed in command of 4,000 government militia and that the "gentlemen of property & men of influence" had provided the Legislature emergency financial backing. The Legislature authorized General Lincoln

In the safest and most effectual manner, to apprehend, disarm and secure, by all fitting ways and means, all persons who, in a hostile manner, should attempt or enterprise the destruction, invasions, detriment, or annoyance of the Commonwealth; and particularly all such bodies of armed men, as then were, or might be assembled in the counties of Worcester, Hampshire, Berkshire, or elsewhere within this state, for the purpose of opposing the authority of the Commonwealth, founded on the laws and constitution thereof.(10)

On January 25, 1787, local militia commanded by General William Shepard of Westfield held the United States Arsenal against a force of insurgents led by Captain Daniel Shays of Pelham. Their object had been to take control of the barracks, weapons and ammunition stored there. Like Captain Luke Day of West Springfield, Shays was one of the Continental Army veterans who had, in the view of members of Cincinnati, abandoned honor and reputation by joining "abandoned men." Shepard was determined to hold the Arsenal "at all hazards." He ordered his artillery to open fire on the approaching rebels "at waistband height." The shots landed in the middle of the advancing column, killing four and wounding twenty. Shays' men retreated in panic and confusion. Those who remained with his army fled through South Hadley first to Amherst, where they received food and shelter from sympathetic residents, and then to Pelham.(11)

Captain Day's men had not taken part in the abortive assault on the Arsenal. When advance units from General Lincoln's army arrived two days later they took part in a night action, crossing the frozen river and routing Day's men. General Lincoln then moved his men to Hadley in preparation for pursuing Shays' forces. On January 30, Lincoln wrote a letter to Shays and his officers demanding that he and his men surrender. The letter, reprinted in the Hampshire Gazette the following day, was stern and uncompromising. "Whether you are convinced or not of your error, in flying to arms; I am fully persuaded that before this hour, you must have the fullest conviction upon your own minds, that you are not able to execute your original purposes." If Shays wished to prevent further bloodshed, Lincoln ordered him to "communicate to your privates, that if they will instantly lay down their arms, surrender themselves to government, and take and subscribe the oath of allegiance to this Commonwealth, they shall be recommended to the General Court for mercy."(12)

When word came that Shays and what remained of his army had retreated to Petersham, General Lincoln ordered a night march. The weather turned stormy and the temperature plummeted. The march became a dangerous ordeal of endurance. When the front of Lincoln's column staggered into Petersham, it took Shays and his men by complete surprise. Panic-stricken and disorganized, many surrendered on the spot. For Shays and his officers, it was every man for himself as they fled across the border into New Hampshire and Vermont.(13)

From Petersham, Lincoln prepared to march west to Berkshire County, to quell remaining rebel opposition there. A final clash in February signaled the end of large-scale, organized resistance. On March 3, 1787, the Massachusetts General Court passed a resolution commending General Lincoln for his handling of the insurrection. The resolution described Lincoln and his men in glowing terms:

the Legislature entertain a high Sense of the Spirit -- Patriotism, and unrivaled Merit of the Officers and, Men who, at the Call of their Country, have, with a chearfulness peculiear to great and good minds, exerted themselves in defense of the Rights & Privileges secured to the Citizens of this Commonwealth by our happy Constitution. The legislature congratulate thier Brethren in Arms on the Success that has crowned their virtuous Exertions for the the Supression of that lawless Insurrection and Rebellion which so lately threatened a total Subversion of those important Rights--(14)

General Lincoln must have been pleased with this public praise. At the same time, he realized that hostility and anger against the government persisted even though the insurgency had been put down. Over and over again, people in many towns provided food for the rebels while he was forced to pay for every requisition he issued. He had intercepted sleigh loads of provisions intended for the insurgents; many more had slipped through.(15)

Although he acted decisively against the insurgents when they were under arms, Lincoln thought the Disqualification Act issued in February of 1787 was too harsh. The act pardoned rank-and-file rebels who surrendered their weapons and took an oath of allegiance to the state, but there were also penalties. Oath takers could not serve on juries, vote, or hold positions as teachers, liquor retailers or tavern keepers for three years. General Lincoln feared that this act would deprive too many of their voice in the state legislature. How could any new grievances be aired constitutionally if they had been deprived of their votes? And, was it wise to further alienate these people? In March of 1787, Benjamin Lincoln served on a commission authorized to extend more moderate terms on a case-by-case basis. The commission pardoned 790 men.(16)

Epilogue

The Massachusetts insurrection deeply disturbed Benjamin Lincoln. He believed a stronger federal government was necessary to stabilize the turbulent politics of the states. Otherwise, the individual republics would fall prey to internal "commotions" like those in Massachusetts. He had an opportunity to vote for a stronger central government when he was chosen as a delegate to the Massachusetts convention that met to vote on whether to ratify the proposed Constitution in 1788. His personal financial circumstances fluctuated, but he remained staunchly loyal to President Washington and the new government for the remainder of his life. General Benjamin Lincoln died in 1810 at the age of 77.

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page