People

Job Shattuck

Job Shattuck

Prologue

While armed Regulators surrounded courthouses and stopped judicial proceedings across the Commonwealth in the summer and fall of 1786, the Massachusetts government looked for answers. It was generally assumed that the people were not capable of acting on their own, and that it took leaders to organize and engineer these confrontations. Only identifying and arresting the movement's key leaders would put a stop to the extralegal gatherings and protests. This line of reasoning would have tragic consequences for Job Shattuck of Groton when the Governor, his Council and representative of the General Court decided that Shattuck was a central figure in Shays' Rebellion.(1)

Like Luke Day of West Springfield, Shattuck did not fit the stereotype so frequently applied to the Regulators by the government and their supporters as ignorant, impoverished debtors trying to escape their creditors. In fact, Shattuck was a well-to-do farmer who owned a substantial house and more land than anyone else in Groton. A veteran of the French and Indian War, he had served with distinction during the Revolution, responding to the Lexington Alarm and fighting at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Shattuck served several militia tours, including the Saratoga campaign, and by 1779 had been appointed Captain. Shattuck's militia rank reflected his social standing in his community; he also served three terms as town Selectman during the war. Job's wife, Sarah, was as committed to the American cause as her husband. Not only did she take on the running of the farm and household when her husband marched to Cambridge with the militia, she joined a band of women who took it upon themselves to capture and detain a known Tory bringing secret dispatches from Canada to the British army in Boston.(2)

When Captain Shattuck decided the Massachusetts government was assaulting his liberties, he responded as energetically as he had during the Revolution. The new state Constitution was barely a year old when Job organized residents to resist to paying a "silver tax" levied to pay the interest on state securities sold to finance the war. The fine he received for his actions did nothing to dampen Job's determination to combat government injustice whenever and wherever he found it necessary. (3)

The Voice of the People

Insupportable taxes and a government that seemed actively opposed to responding to the grievances of the people were all the encouragement Shattuck needed to join the Regulation in 1786. Fifty years old, his age, experience and the local respect he commanded made Captain Shattuck a formidable ally. The Court of Common Pleas was to meet in Concord in September. Determined to stop the court, Shattuck arrived not just with men but wagonloads of supplies. He set up a Regulator encampment on the Concord green. The hundreds of Regulators arriving from surrounding counties clearly outnumbered the friends of government.(4) Job Shattuck signed and delivered to the judges a message on behalf of the assembled Regulators:

The voice of the People of this [Middlesex] county is that [the court] shall not enter this courthouse until such time as the People shall have redress of grievances they labor under at present.(5)

The Massachusetts government responded with anger and alarm to the Concord and other September court closings. Governor James Bowdoin already had issued on September 2 a stern proclamation in reaction to the forced closing in August of the Court of Common Pleas in Northampton by Captain Luke Day and hundreds of armed Regulators. The Governor had directed the state's Attorney General, Robert Treat Paine, "to prosecute and bring to condign punishment the Ringleaders and Abettors of the aforesaid attrocious violation of law and government; and also the Ringleaders and Abettors of any similar violation in future, whensoever or wheresoever it shall be perpetrated within this Commonwealth."(6)

Now, in the wake of the new court closings, the General Court passed three harsh acts designed to control and halt the escalating insurgency. The first was a Militia Act passed on October 24. It declared that "any officer or soldier who shall begin, excite, cause, or join in any mutiny or sedition" would be court-martialed. A Riot Act followed on October 28. It forbade gatherings of more than twelve armed persons and empowered county sheriffs to stop riots by force, killing if necessary. Finally, on November 10, the General Court passed an act suspending Habeas Corpus until July, 1787. Under the terms of this act, the government could arrest and hold for any length of time without bail anywhere in the state any persons "whom they shall suspect is unfriendly to government."(7)

A Bloody Day With Poor Job

By now, the government had begun to identify the men they believed were responsible for inciting and leading the unrest. Job Shattuck's name was high on the list. On November 29, a company of mounted militia set out from Boston with a warrant for Job's arrest.

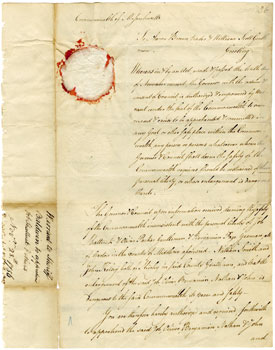

On November 28, 1786, Governor Bowdoin and his Council issued this warrant "to

apprehend Job Shattuck & others."

More info

When they did not find Shattuck at his home, the militia followed his tracks in the snow. They cornered him on the bank of the Nashua River. Hopeless as his case must have seemed to him at this point, Job Shattuck resisted capture with characteristic courage and determination. He grappled with one man, while trying to draw his sword. Shattuck dropped when another militia man slashed him behind the knee with a saber, slicing through cartilage and ligaments. Blood stained the snow as the militia loaded their grievously wounded prize into a sleigh and drove to Boston. It had been, Job's friend James Parker of Shirley wrote in his journal, "a bloodey day with poor Job."(8)

Captain Job Shattuck refused to surrender until severely wounded by a saber cut to his

knee.

More info

In the words of George Richard Minot, arresting Shattuck was "an important event." Minot's History of the Insurrections in Massachusetts was the first published account of Shays' Rebellion. According to Minot, Shattuck's capture produced excellent results for the government. "The heart of the insurrection in Middlesex was broken by so sudden a stroke, while the friends to good order received a confidence from the strength and success of their cause." (9) A song published in the Worcester Magazine light-heartedly referred to Shattuck's injury and its supposedly demoralizing effects on the Regulators:

Yet dismal to read!

Our poor brother Shattuck,

Was fell'd with a mattock, Heigh Ho!(10)

The Regulators would not have disagreed with Minot. Shattuck's brutal arrest was indeed "an important event" from their perspective. For men like Daniel Shays it meant that "The seeds of war are now sown."(11) Rumors flew that women and children had been roughly handled, even maimed, in the course of the November arrests. Others were sure that Job Shattuck was dying for want of proper care. Uncertainty about Job's fate and whereabouts fueled widespread anger and hostility. Because of the suspension of Habeas Corpus, Shattuck and the three other Groton men arrested at the same time were imprisoned far away in Boston rather than in the Middlesex County jail at Concord. Under the terms of their confinement, their jailer was forbidden "to offer any Person to Speak to them or to have any Communications with them and not to permit them the use of Pen & Ink or Paper without the special leave of the Governour."(12)

Job may indeed have suffered from want of medical attention in the early days following his capture. The broadsword had gashed the cartilage behind his knee, immobilizing him and making the long sleigh ride to Boston an excruciating ordeal. Once in Boston, it was four days before the Governor's Council ordered Shattuck's jailer to provide him a bed, bedding and a nurse.(13)

Gallows or Pardon?

Shattuck languished in prison through the long and turbulent winter of 1786-87, while the government militia eliminated organized Regulator resistance. Shattuck petitioned to be released from confinement until his trial. His wounds were not healing well; lack of fresh air and exercise were also hurting his health. His community also pleaded that Shattuck be allowed to return home pending his trial. That organized resistance had ended following a final confrontation in Sheffield on February 27 probably influenced the government's decision to allow Job to come home. Job was released on bail on April 6, 1787, after four months in jail.(14)

In May, Job Shattuck was tried with Oliver Parker, also of Groton, on charges of high treason..(15) The government charged that "Job Shattuck of Groton in the County of Middlesex Gentleman…did devise and conspire to levy war against this Commonwealth and then and those with a great Number of Rebels and Traitors against the Commonwealth." The Court accused Shattuck "of being moved & seduced by lawless and rebellious spirit, and withdrawing from the said Commonwealth that cordial Love and due Obedience, Fidelity and Allegiance which every member of the same Commonwealth of Right ought to bear to it." Further, Shattuck stood accused of

most wickedly and traiterously devising and conspiring to levy war against this Commonwealth and thereby most wickedly and traiterously intending as much as in them lay to change and subvert the Rule and Government of this Commonwealth duly and happily established under the good People the Inhabitants and Members of the same according to their Constitution and Form of Government of the same, and to reduce them to Anarchy, lawless Power and Confusion.

Both men pled not guilty, but the jury acquitted only Parker. On May 9, 1787, the Supreme Judicial Court for Middlesex County issued its verdict. On the recommendation of the attorney general, the court sentenced Job Shattuck to death and ordered "that the said Job Shattuck be taken to the Goal of the Commonwealth from whence he came, & from thence to the place of Execution & there be hanged by the neck untill he be dead."(16)

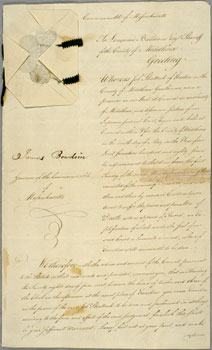

Sheriff Loammi Baldwin was ordered to hang Job Shattuck on June 28, 1787 "between the

hours of twelve and three of the Clock in the afternoon at the usual place of

Execution."

More info

Only a pardon from the Governor could save Job Shattuck now. Fortunately for Job, that same spring John Hancock was elected as governor in a landslide. The people of Massachusetts had had enough of the unyielding policies of the Bowdoin administration, and Governor Hancock was prepared to accommodate them. He issued numerous reprieves for sentenced Regulators, including Job Shattuck. The shadow of the gallows still loomed, but his execution day was moved to July 26.(17)

The postponement must have given Job cause for hope. A reprieve was only one step away from a pardon, and Hancock had been liberal in forgiving rank-and-file Regulators. Hard liners like Samuel Adams continued to argue, "the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death,"(18) but Governor Hancock was clearly of another opinion. That summer, he cemented his popularity with the people when he issued pardons to all but two of the condemned, including Job Shattuck.(19) Even Jason Parmenter of Bernardston, charged with the murder of Jacob Walker, a government militia man, went free. Of all the Regulators sentenced to death, only John Rose and Charles Bly were hanged, for looting. Tragically, both men seemed to have believed that they, too, would eventually be freed. John Bly declared that since his imprisonment, "I had been conducted as if I was never to be executed." Job Shattuck could hardly have said the same.(20)

Epilogue

Captain Job Shattuck returned to Groton a cripple. The man known for his iron constitution and energy walked with a crutch for the rest of his life. His wife, Sarah, died in 1798. Shattuck died in 1819 at the age of 83. The large three-story house he built on the banks of the Nashua River still stands.(21)

About This Narrative

Note: All narratives about people are, to the extent possible, based on primary and secondary historical sources.

See Further Reading for a list of sources used in creating this narrative. For a discussion of issues related to telling people's stories on the site, see: Bringing History to Life: The People of Shays' Rebellion

| Print | Top of Page